A while ago I wrote an article on how to make quick Chip Tune music for your game using free and open-source software. Well, that was all well and good and everyone made some suitable music for their games. But now we need to get a little more in depth.

In this article, I’ll show you some very basic music theory and a couple techniques that you can use to evoke particular emotion and feeling in your music. With these techniques and theory, you can begin to apply it using the Chip-Tune synths from the last tutorial and branching into more orchestral-sounding music.

If you haven’t read the previous article, I suggest your start there. We’re going to work off of what we learned from there.

What’s the difference between feeling and emotion

To be honest, I couldn’t think of a better way to lay it out. Basically, your music can be energetic and lively; or maybe it’s mellow and pondering. That’s the feeling. The emotion in the music is happy, or sad. I guess really they’re one in the same in a lot of ways, but I needed a way to break out the different things you can try to achieve, and these words seemed as good as any others.

A little distraction

Try this for fun: Take your song from the last article, and replace the instruments with some free VSTs (listed below). Here’s my track from the first article, redone with new instruments.

That’s a major sound difference, right? This is just replacing the synthesizers we were using before with some instruments from DSK Virtuso (free VST). I could further play with this by changing the velocity of the notes being played (how forceful they are), maybe change some of the BlueARP settings, but there’s already a big difference in feeling by replacing instruments only.

This is a perfectly valid way to start making orchestral sounding stuff. Just use different VST instruments.

Achieving feeling in your music track

There are a few ways to achieve different feelings:

- As mentioned, try using different instruments because every instrument provides a different feeling. There’s hundreds of examples and I’m sure you can think up more of your own, but to get you started:

- Synthesizers give a modern or futuristic feeling

- Snare drum rolls can give you a militaristic feeling

- Industrial sounds give you well, an industrial feel

- Slowly building strings give you a grand sweeping sense of scale

- Picolo and flutes can give you a light-hearted, adventurous feel

- Soundscape pads are great for sci-fi feeling

- Adjust the tempo. The faster a song is, the more energetic it will feel

- Change the density of notes

- Sparser notes give a more distant and abstract feeling

- Dense notes are busier, more active pieces

- Use different effects

- Reverb can help give a piece of music more scale

- Delay and echo can make the scene the music is in feel larger or more enclosed

Getting emotion in your music track

While not the be all and end all of emotional expression in music, the key that a song is in can be a decent starting point for an emotion. Musical keys are groups of notes that form a scale, one of these notes is the tonic and the key is therefore named after it. There’s a lot of theory behind keys, but we can get it right down to some basics.

First, let’s cover some notation

Western music notation can get complicated, but we’ll just stick to the basics. Absolute basics, just enough to get through some of this stuff. To be 100% honest, you can get through without worrying about the notation, but for some people, I know it helps to see the notes being played, and the best way to do that is show the notation.

If You’re Not Interested

in reading music, just skip this section. I talk about notation in a few spots that you can ignore if you like.

It’s not super difficult. Time goes from left to right, you play each note as it comes along. Different notes have a different amount of time. Here’s a piece of music, it’s an F over and over again. But each note lasts for a different amount of time. Listen to the track and move to the next circle after each note.

MusicSheetViewerPlugin 4.1The first note is called a semibreve and it’s a whole note because it lasts for 4 beats. The second note is a minim and it’s played for 2 beats. In this piece of “music” the time signature is 4/4, which means there are 4 beats to every bar (bar is a measurement of music, it’s the vertical lines), and that each “beat” lasts for a quarter of a note (the second 4 means one 1/4).

The third note is a crotchet which lasts for exactly one beat. So four of them fit into a bar. Then there’s the quaver which you guessed it, lasts for half a beat, and the a semi-quaver which is a quarter of a beat. These guys are connected simply because when they’re on their own, they look like a crotchet but have a little tail (or two tails for a semi-quaver) coming off the top of the stem. If they weren’t connected it would just be harder to read the music (to many lines all over the place).

The next thing to understand is pitch. These go up and down. Low notes on the bottom of the stave and high notes on the top (the stave or staff is the horizontal lines). Each position in those lines is a particular note, you know which note based on the clef used. The notes will become apparent shortly.

Tonic

As mentioned, it’s the base note/first note of the key. It’s the most important note of the key, and that’s why the key is named for it. You can think of this note as the final note, a piece of music is resolved when the tonic is played.

The way it works is that playing other notes causes a sort of tension to build, and the listener doesn’t get relief until that tonic note is played. As an example, here is a C Major Scale:

MusicSheetViewerPlugin 4.1Now, listen to those notes a few times. Next, here’s a short piece of music that plays some of these notes. Notice how the piece doesn’t feel complete until that last C is played. That tonic note is resolving the song. This is an important concept, the other notes are dancing around this tonic.

MusicSheetViewerPlugin 4.1Do you feel how that final note completes the piece? If not, try listening to it but pause before the last note is played. You can play with this effect too, remember, the listener is expecting this note, so you can draw the piece out, take the listener along, but making them think you’re going to hit that note, but then you don’t.

When you do hit that note, hit it hard, crash down on it. That’s how good it feels for the listener to finally hear it.

Some more talk on notation

The swirly thing at the very start is a clef, this particular one is a G-clef and specifically a treble clef. There are other clefs, F-clefs, and C-Clefs. What they indicate, is that their starting point (the second line from the bottom in the case of treble clef) is the note they’re named after. So second line from the bottom is a G in the case of the treble clef (because it’s a G-clef). It can be moved up and down, meaning that the G is on a different line, or gap between lines.

This is used because different instruments have different ranges of notes. If all the notes your particular instrument can play are way up high, you don’t want to use a treble clef because then all your music is way above the stave. You would’ve noticed that notes that fall below the stave get a little line through them, that’s just a helpful line for the reader to guage just how far down that note is; it works the same going up.

There’s also a 4/4 time signature which we’ve talked about. But you see that curved line connecting the two crotchets? That just means the one note continues into the next note without breaking; causing those two crotchets to be played as a single minim. We had to do that because we ran out of beats for that bar, the bar being indicated by the thin vertical line across the stave.

There’s one last symbol, a short, thick, horizontal line at the end. That’s a rest that lasts for the span of a minim, two beats. A rest meaning, chill out musician, you don’t play any notes.

Major or minor

A key can be in one of two modes. Either Major or minor. If someone just says “We’re in the key of C”, it’s assumed that they mean C Major (I don’t know why, but that’s just the way it is [things will never be the same]).

The mode is super-duper important and is what’s going to give you the most feeling for the least amount of work. You remember our C-Major Scale from before right? Here it is again followed by a Perfect Authentic Cadence (two chords that sound like the end of a song).

MusicSheetViewerPlugin 4.1Well, here’s the C-minor Scale:

MusicSheetViewerPlugin 4.1What a minor key does is it provides a much more sombre emotion to your music. It can also be described as serious or melancholic.

This isn’t a hard and fast rule, not by a long shot, but it’s a good… indication for us when we’re just starting out. Major keys for happy music, minor keys for sad music.

What’s the difference between Key and Scale?

I might have used these interchangeably in a few places, and I apologise. I shouldn’t have because they do mean different things, but to be honest, it doesn’t matter much.

The Scale is simply the arrangement of notes from a key, in an orderly fashion. From bottom to top, or top to bottom.

The Key is the notes within the scale. But they’re not in any particular order. Think about it; a piece of music can’t be in a scale because that would sort of mean all the notes were in the same order all the time.

What are those funny ‘♭’s?

Those are the key signature. You’ll note that the C-Major and C-minor keys have the same notes… sort of. They sound different. The little ♭’s, and you’ll see ♯’s for some keys, denote that the note on that line of the stave is to be flat or sharp (this is why C# language is C-Sharp and not C-Hashtag or C-Pound).

The only difference between keys in music is a different combination of sharps and flats. The only notes that exist are A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. It wouldn’t matter how many different ways you played these base notes, or which note you started on, everything would be in the same key. By sharpening or flattening some of these notes, we produce different keys.

But which key?

I suspect you can just start by placing some notes down on your piano roll until something sounds good. That’s one way to do it. Keep adding notes, and instruments, that sound good and you’ve got yourself a peice of music. What key it’s in is irrelevant and comes later, because the key is only serving the notation.

We’re modern people, we don’t need to write all the music down in order for it to be played. We have VSTs for that. If it sounds good, the music notation is secondary and means nothing anyway.

Another way to do it is a little more structured, and personally it’s what I do:

- Find a piece of music I like that I want to vaguely have the right feeling of

- I analyse it as best I can to try and discover what makes it sound the way it is

- By playing some notes on my piano roll, I can determine what key it’s in

- I start by making my music in that key; I look up the chords within that key and I go from there

What’s a chord?

A bunch of notes played together. Generally speaking, you play notes from the key that your music is in. For example, in C Major, I could play the C, E, and G notes together and it sounds good. That’s because these notes are separated by a certain amount of space. The tonic is the first, the second note is skipped, but we do play the third, and you guessed it, the fifth note of the key/scale (they’re all present in the scale)

Roughly speaking, if you separate your notes at about those ranges from notes in a key, it will sound good. This also means that different instruments can be playing these different notes at the same time, sort of producing chords, playing in the same key, and generally sounding good.

You might be familiar with a song titled Halleluja by Leonard Cohen? There’s lyrics in that song that describe the chords above.

You cannot make music evoke a feeling by using a particular key. I know I said before that Major == happy and minor == sad but this is only true on a very very superficial level. There is music written in D minor that sounds happy, and you can make C Major sound sad.

There are web pages that will tell you the emotions evoked by certain keys. This is true only in the sense that historical composers tended to compose movements in their music in certain keys and consistently created music with the same feeling. So it just kind of became the norm that C minor was longing and lovesick, but only in the context of the music written in that time.

Writing More Complex Music by Combining Instruments

To start making more complex music than what we did before, we can start by adding more instruments. Previously we had two synthesizers, which isn’t a lot of different sound. Unfortunately, you can’t always lay a bunch of generated melodies on top of each other; though you can certainly use that as a starting point and adjust from there.

But let’s try something different. Let’s make our own little melody. I’ll take you through the process I have in creating a short little bit:

- I start by thinking about the instruments I want and the key I want

- I write the score (which just means the sheet music)

- I keep going until I’m happy with it, often referring to chord charts

- I export the midi file so that I can play with it in my DAW, possibly adding affects etc

Keep in mind that this is my process and you can’t steal it. Kidding, but you want to play with it so that it works for you. Your own method will then evolve over time.

The Instrument Selection & Key

To select the Key, I just throw a dart. Unless I know exactly what I want, which I never do, I just pick a Major key for a happy track, or a minor key for a sombre track. We’ll then take it from there.

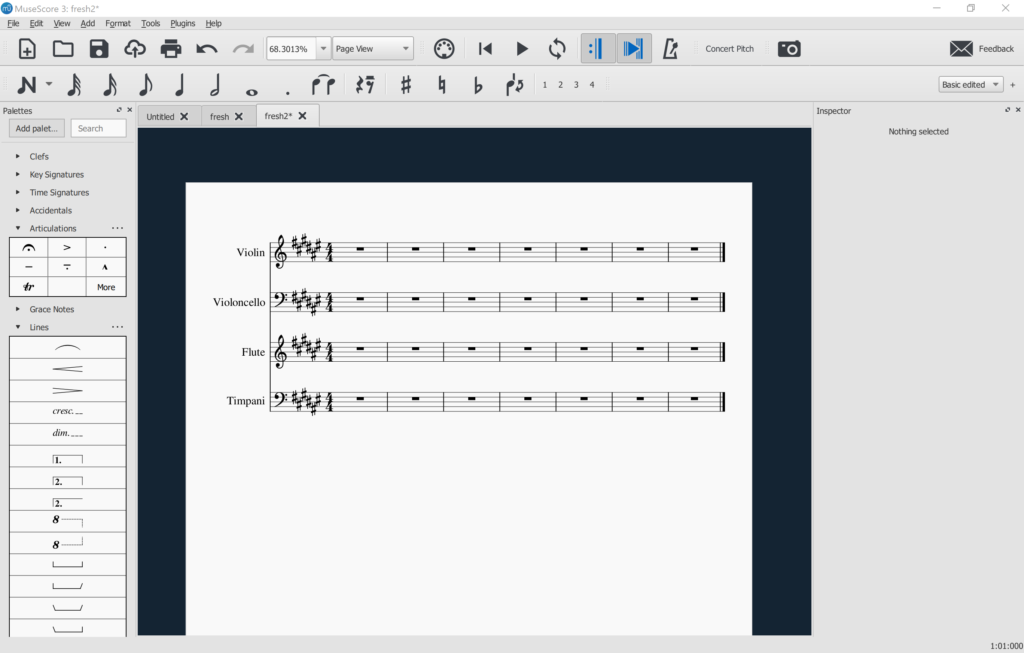

As for the instruments, it depends completely on the feeling. For this, I want to make the start of a somewhat-orchestral sounding track. With that in mind, I will use:

- Violin

- Cello

- Flute

- Timpani

It’s a simple as that. I tend to always start with four instruments because I find that’s a good round number to get a complex enough sound, but not so complex that I can’t manage it (I’m not a composer, I make games). It is also super easy later on to replace the violin instrument with an ensemble instrument (we’ll talk about that later) to get a more “rounded” sound.

Writing the Score

As I said, this is my process. If you can’t read sheet music (I didn’t show you a lot above), or you’re not interested in learning it (it’s basically a new language), then you will need to figure this bit out a different way. I would suggest playing with the piano roll in your DAW (I use Ardour because it’s free and open source).

To write my sheet music I use MuseScore which is free and open source. So in MuseScore I will create a new peice, add my four instruments (or instrument proxies if I plan to replace “violin” with “saw-tooth synth” later), and my key.

This is the most time consuming part: we make some music.

Starting the piece

In my head, I have a very simple intro in mind. It would be the introduction to a longer piece, but I just want to keep things short for this article, so I’ve only got 7 measure in there. I want there to be a very simple, probably quiet, violin playing long drawn out notes, that is then interspersed by a cello and timpani. A flute then joins in to build up the music before the timpani takes over, prepping us for the next part. I likely would have two chords being used in the whole thing.

I don’t know exactly what I want everything else to do, but I know I want that quiet violin playing two different notes. So I’ll lay those down first.

MusicSheetViewerPlugin 4.1Even more notation

The little p means “quiet”. You can also have an f which means louder. These can also be double-quiet with pp and super quiet with ppp (same with the f‘s). It’s also possible to have mp and mf, which mean “moderately quiet” and “moderately loud” respectively.

The curvey line is same as before, the note continues on. So this is one reaaaaly long note stretching across several bars/measures.

Adding a bit of melody

I like using the cello as the melody a lot of the time, I just think it sounds good. So, I just hum it out and place the notes to match.

MusicSheetViewerPlugin 4.1I’m not placing things randomly, just so it’s clear. I look at my first note playing with the violin, it’s an A# and I’m in the key of D#. So I load up a website like this one and look at what chords are within the D# key and find chords with an A# note played in them. My goal, is to use my other instruments to play some or all of the other notes in one of those chords.

Okay, so my A# could be used in:

- D# minor – The tonic (I) chord using D#, F#, A#

- F# Major – The III chord, using F#, A#, C#

- A# minor – The V chord, using A#, C#, E#

I’ll stick with the tonic chord. If you look at that first run of the cello, I’m playing notes in this order: D#, G#, F#, A#, F#, D#. You will notice that all of these notes, except one, are in the D# minor chord. That outstanding G# is, i think, known as a nonchord tone, but I could be wrong. I just think of it as another note that sounds good. I use it there to build upward toward that A# but allowing me to do the up-down stepping that I wanted.

The second run of the cello is almost the exact same thing, but I’ve just added another note to embelish it. That single note makes the music a lot different, imagine how it would sound without it.

The final run there of the cello is the same as the first run, but it’s transposed up to match the new baseline note of the violin. The violin is now playing a C#, which means altogether the two instruments are playing an F# Major chord. The second chord from the above list.

So in total, we’ve moved from I to III (chord I to chord III in D# minor). The way you move around these chords plays a big part in how your music sounds. There’s a lot of theory you can read about this, but I sort of just try to stick around whatever the current chord is. The chord might change halfway through a measure etc, and change often, but overall, if I needed to hum this song, what note would I be humming? That humming is the overall sound, the overall note/chord being played.

It’s also important to sort of stick around a single note. The tonal centre of the music. This is where the theory of musical keys starts to fall apart and you realise that so long as you head back toward your tonal centre, it doesn’t matter what the key is.

Putting in some drums

The Timpani, if you didn’t know, is an orchestral drum. It’s the sort of thing that gets rolled on to build up to a climax, it gets beaten out to make kind of tribal-sounding stuff.

The way I want to use it is like a sort of response to the cello. This is another important part of music called the call and response. Pop-songs use it a lot, so does rock. You know what, it’s everywhere. You can read about it here a bit.

In order to respond to the cello, the timpani is going to be a short, rapid response. It’s also going to gradually build up in each response. If I continued writing this peice, the timpani’s responses would become more complicated, would involve other percussion instruments, and would probably start to bleed into the cello’s calls.

The effect would be like the cello is calling out before the timpani has even finished responding. The cello is insistant, and would start to become less calm (more complicated melody). The timpani would become angry or frustrated. Together, they would build up enough to allow more instruments to come in etc. But I’ll leave all that up to you.

MusicSheetViewerPlugin 4.1With that done, there’s only one last instrument remaining.

Adding another instrument to the melody

When adding another “lead” instrument, like this flute, there’s two ways I could go about it. The cello could take a back seat, play a much simpler few notes to fill-out the chord, or I could add it to the melody.

I opted for the later. It’s hard to do this, at least I find it hard. The trick I’ve learned is that all the instruments that are playing melody should not be competing with each other. This usually comes to mean less notes, less dense, with rests in between notes here and there.

This is what I came up with:

MusicSheetViewerPlugin 4.1Right there it’s only one phrase, but I think it works with the cello, and if I were to extend this piece it could easily continue to work with the cello the way it has been.

That’s all I will do as I only wanted to illustrate my process of writing the music. It feels very incomplete, but that’s intentional. You can complete it. Don’t worry about adding more instruments, just have the violin play a more active roll while the cello takes a back seat.

Completing the track in the DAW

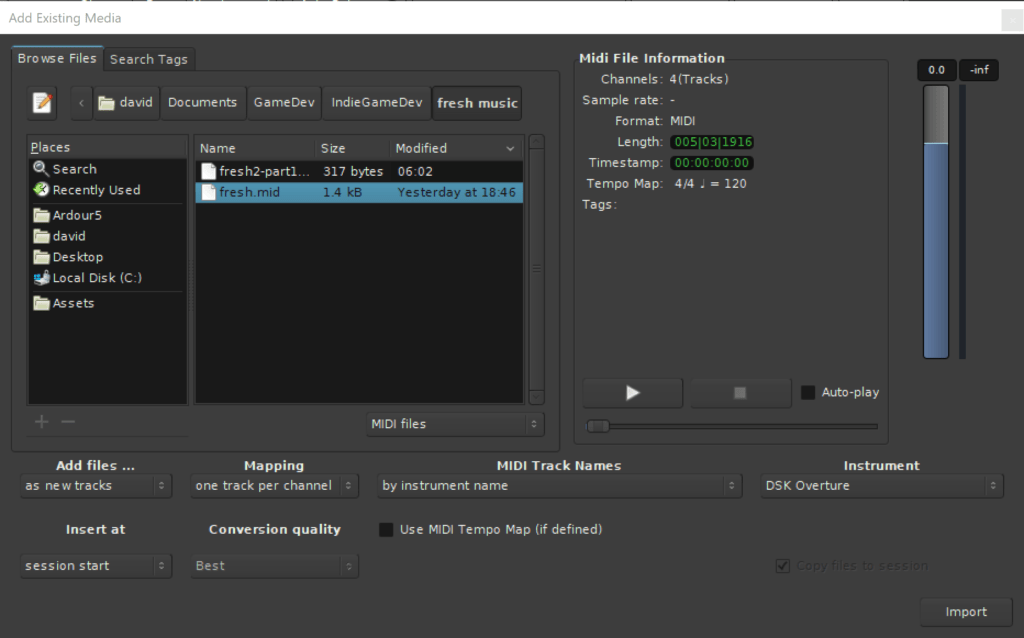

The last step is to export the MIDI file from MuseScore and load it into Ardour so that we can use a better sounding instrument than your computers MIDI synthesizer (which is what all these tracks so far have been).

From MuseScore just go to file > export and export a MIDI file. Very simple.

Create a new session in Ardour and go to Session > Import or press Ctrl+I. Find your MIDI track and Add files… as new tracks, Mapping one track per channel, Midi Track Names by instrument name, and insert at session start.

The most important selection is the Instrument. Get yourself DSK Overture, another free VST, and select it.

Ardour will think for a bit and then create your tracks. The import window stays open after import, so just close it. Fiddle with the timeline on the very bottom to zoom in and see our whole song.

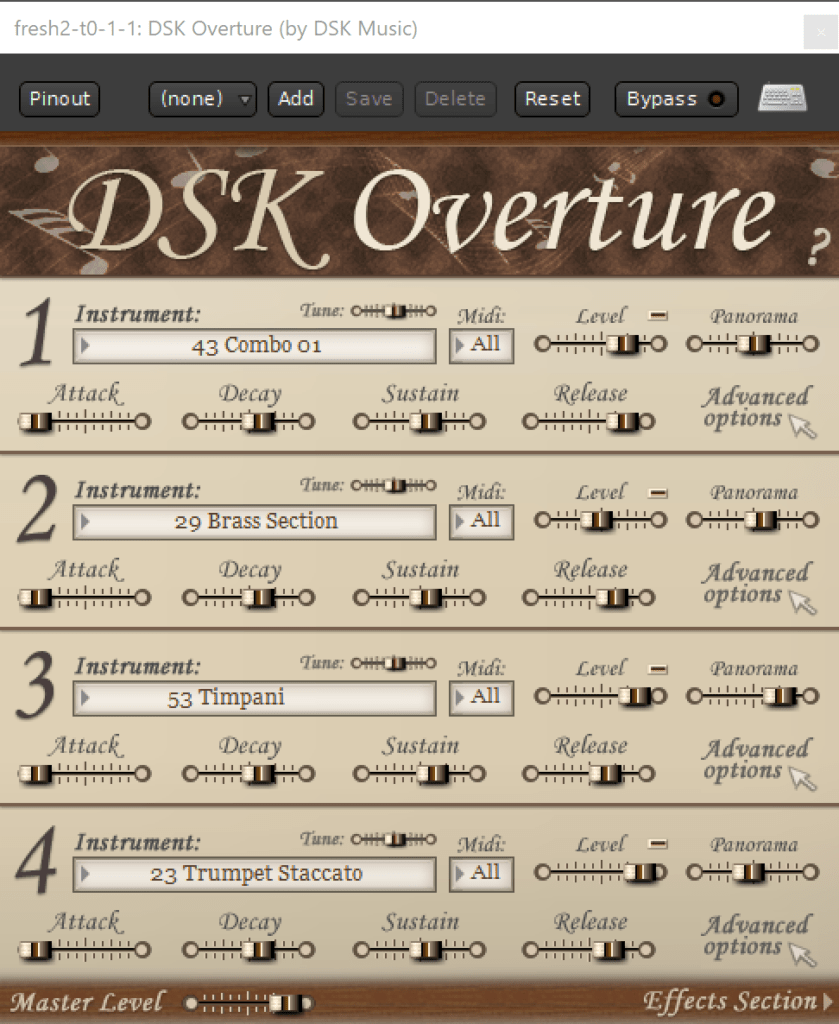

You can hit play now and listen to what it’s done. Not what you thought right? That’s because on it’s own, DSK Overture has just loaded some instruments, we just need to edit the VST plugin settings for each track to give it the instruments we want.

Remember those plugin doodads from the last tutorial? Go and open up DSK Overture in the first instrument, it will look like this:

So you can see it’s playing a “Combo” whatever that is, a whole brass section, our timpani and staccato trumpet all together. Man, we just want some violin. So remove instruments 2, 3, 4 but setting them to 54 <<empty layer>>. Then change the first one to a String Section P (38). We are using a section, because it’ll give us a more rounded-out sound than a single violin.

Back in Ardour, set this violin track to be played “solo”. This means that all the other tracks are muted, we’ll fix them up later.

Play your track, it should sound like this:

Okay; so that’s good. Now set the cello track to solo and adjust DSK Overture in the same way, but select a single cello (30). Now if you play it, it sounds a little funny. The notes bleed a bit too much. This is the “release” setting on the instrument, dial that down to the middle of the slider.

You should end up with this for the cello:

Then if you set them both to solo (I know right, how can they both be solo?), you should have something like this:

Now, add your Flute on the third track, remember, you need to set the release down a little and do the same for the timpani. I used Flutes Legato (8), again, for more complete sound. You’ll end up with something like this:

What’s next?

Well, that’s it for this article. You can take it from here, and make a more complex, longer, and more interesting 4-instrument music track. Four is a good number to start with, leaves you with lots of opportunity to do interesting things, but won’t get too much for you to manage.

Remember to try out some different instruments as well; use a synthesizer and an electric guitar combined with a tuba. You can make very interesting sounding music by playing with the instruments, even when your melody is relatively simple.

Don’t forget our old friend Melody Generator 2 from the previous article. Sometimes you just need to make a music track, and that will help you get a start on things.

There’s a lot of theory and notation as well. The notation is a little less important, but you’ll need it if you want to learn a lot of the theory, which is super important. Floundering away like we have in this article will get you to the point of having nice sounding music in your game. But if you want to take it beyond that, you’ll need to study music like you would any other subject.

Hey, who knows, you could be the next Nobuo Uematsu. He was self-taught too you know? I’d love to hear what you come up with, so please, let me know in the comments or on twitter.

In the next article we discuss making safe-zone music for your game so that everyone feels warm and comfortable.